EXCURSION 1: Morris Hastings' liner notes for the Columbia Masterworks LP Set MX-300, 1948: Vaughan Williams – Fantasia on a Theme By Tallis, performed by the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Dimitri Mitropoulos:

"Of all Twentieth Century British musicians, Ralph Vaughan Williams is perhaps the most individual and yet the one in whose works the listener can best sense the stately procession of English music from Tudor days to the present. Vaughan Williams’ musical style might be said to be a compound of enthusiasm for and knowledge of English folk music, plus an extraordinarily flexible scholarliness, plus a mysticism that often finds eloquent expression in poetry of a high order.

Vaughan Williams’ feeling for the great tradition of his native music is splendidly exemplified in his Fantasia On A Theme By Tallis, so knowingly performed on these Columbia Masterworks Records by the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra under the perceptive leadership of Dimitri Mitropoulos. This beautiful composition is based on a theme written by the Sixteenth Century English composer, Thomas Tallis, sometimes known as “the father of English cathedral music”.

In Tallis’ time eight musical modes were employed in ecclesiastical music. To each one of these modes Tallis’ contemporaries assigned a distinguishing characteristic, as set forth in the Sixteenth Century verse:

“The first is meeke; deuout to see,

The second sad: in maiesty.

The third doth rage; and roughly brayth,

The fourth doth fawne; and flattry playth.

The fyfth delight: and laugheth the more,

The sixth bewayleth: it weepeth full sore.

The seuenth tredeth stoute: in froward race,

The eyghte goeth milde: in modest pace.”

[Author's note: The eight modes are I. ionian - II. dorian - III. phrygian - IV. lydian - V. mixolydian - VI. aeolian - VII. locrian - VIII. hypomixolydian]

In 1567 Tallis wrote a set of eight melodies for the Metrical Psalter of Matthew Parker, then Archbishop of Canterbury, each illustrating one of the foregoing modes. It was on the third of these melodies that Vaughan Williams elected to base his Fantasia, written in 1910 for the Gloucester Festival. To modern ears, however, there seems far more of tranquillity and devotion than the raging and rough braying that Tallis and his colleagues presumably heard in it.

The Fantasia is scored for double string orchestra, with four solo strings – two violins, viola and ‘cello. The second “orchestra” is formed, according to the composer’s instructions, of two first and two second violins, two violas, two ‘cellos and one doublebass. The first “orchestra” embraces the other strings of the ensemble. There are passages when the solo instruments are heard as soloists, others when they play as a group, still others when they mingle and blend with the larger orchestra.

The Tallis theme is outlined first by the lower strings, then played in its complete form by all the violas and second violins and half the ‘cellos and basses below and the first violins above in octaves. A set of free variations on the theme follows.

Scott Goddard has written illuminatingly about Vaughan Williams’ Fantasia: “If we study the Tallis Fantasia,” he declares, “the design of the single long movement is seen to be as simple as is the harmonic scheme through which Tallis’ noble Third Mode melody pursues its endless way. The great chords are removed from position to related position among a series of modal harmonies; they return inevitably and soon their place of origin as though impelled by gravitational force. There is about the Fantasia a sense of intense deliberation. Its dynamics are as restrained as its harmonies. Weight of tone more than loudness gives emphasis… For the listener who can give himself to this music it has the force of a revelation, the immediacy of the mystic’s vision.”"

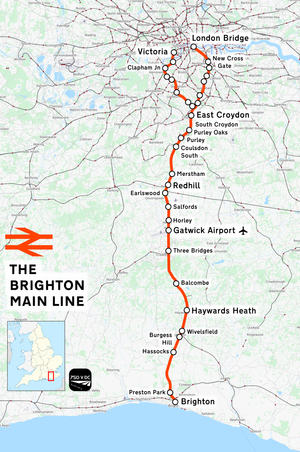

A little less than nine months after the English composer Gustav Theodore Holst, born 1874, had passed away on May 25 1934, a boy named Royston Michael Wood was born on February 20 1935[1] in Thornton Heath[2], County Borough of Croydon, to his mother Constance Wood (née Moreton) and his father Charles Sidney Wood[3,4]. Although today Croydon belongs to Greater London, it was still part of the English county Surrey then, and had its origins as a small country town. In the wake of the industrialisation its population exploded, when the installation of new roads and train connections between Brighton and London established it as a commuters' settlement for people working in London. In 1920 London's first airport was built on Croydon's greenlands, and Croydon's infrastructural relevance for London increased further. When Royston was born, Croydon - although it was still the northernmost district of Surrey - had effectively transformed into London's southernmost suburbia.

Constance was described by Royston as a Reigate „village girl“[5] whose father had held a post office[6]; it is likely that Royston’s maternal ancestors had their roots in Reigate, too. One historic newspaper article gives a likely glance into her earliest days: a certain Constance Moreton received two awards in a children’s cookery competition on the occasion of the Reigate Industrial Exhibition of July 1916, as the Surrey Mirror and County Post reported - a second price for a milk pudding, and a first price for plum cake made with dripping; although it is unclear if this young lady was in fact Royston’s mother, the age and circumstances would fit[7]. In her youth Constance had developed a fondness for light classical music and a talent for singing opera, and had thus started working as a semi-professional opera singer for the Carl Rosa Opera Company, a touring ensemble founded in 1873 by the German impresario Carl Rosa (1842 – 1889), which presented light opera music to paying audiences and continued its touring activities under the same moniker after Rosa’s death. A picture of the Opera Company from 1922 is unlikely to feature Constance, but shows an artistic society of fur-coated ladies and sharp-dressed gentlemen far removed from the world of rural cooking competitions: at least for a while the “village girl" from Surrey got a taste of the wide world and a touring musician’s colourful life. “Mum wasn’t a music nutcase”, Royston remembered, “but she had a lot of music in her, she’d been a very good singer”, as well as an amateur pianist[8]. When she became a mother, Constance’s days as a touring musician had come to an end; from then on she became a full-time housewife, taking care of her children and family. The sources suggest that she had inwardly finished with her half-flamboyant past, and few people were even aware of it[9].

Royston's father Charles was a „Yorkshire-born Lancashire man“ whose “parents had moved down to the country from Leytonstone to settle around Redhill”[11], suggesting that at a young age he had already come a long way – at least for the conditions of his time. One vague source states that he was a metropolitan policeman, which is the only available piece of information about his profession. Indeed, the National Archives Of The UK mention that a man named Charles Sidney Wood was working as a metropolitan police constable in the Z division (Croydon) from August 22 1927 to March 19 1939, which encompasses Thornton Heath; since there is evidence that the Woods left Surrey in 1939, there is some likelihood that the same person might have been Royston’s father[12]. Like his wife Constance, Charles was an ambitious amateur musician who had played an undisclosed wind instrument and had also served as the grandmaster of the local Reigate Village Band[14], by which Royston probably meant the Reigate Town Silver Band, which the online archive Reigate History describes as an "excellent band" that "performed on Saturday nights in Market Square (by the Old Town Hall)", and that held rehearsals "in one of the caves off Tunnel Road"[10]. However, Charles “lost his teeth[, ...] couldn’t play any more and retired”[13]. It appears as if this unfortunate situation occurred around the time when Royston was born, and that Charles was not playing music anymore when Royston was young. The description of Charles' background as a band-leading policeman gives the impression of an intelligent man who was also graced with an artistic trait and leadership qualities.

Overall, Royston described his upbringing as „lower middle class”, and his parents both as “Surrey village stock“ and „very straight, very unadventurous yeomen stock“[15]. He grew up with two siblings, his sister Diana, who might have been the eldest sibling and about whom no further information exist[16], and his brother Graham Clifford Moreton, who is younger than Royston[17]. As Royston was not known to speak a lot in public about his parents and siblings, most information about his family come from his family members. Their recollections especially draw the attention towards the use of names in the family. Royston, for starters, was known to characterise his own first name as peculiar; for some reason, his parents never referred to him as Royston, but always used his middle name, Michael[18]. Conversely, Royston, when talking to his children in his later life, used to refer to his brother Graham, who had apparently inherited his mother’s maiden name as his third name, as Uncle Moreton[19]. Whether this odd nomenclature was an example of Royston’s eccentric humour, or whether it had its roots in family history, is unknown.

As previously noted, Royston's homeplace Thornton Heath, which Royston later described to a folk club audience as “a sort of suburb of Streatham, which is a suburb of somewhere else, which is a suburb of somewhere else”[20], still belonged to Surrey at the time of Royston’s birth, and only got integrated into Greater London in 1965, which means that Royston was not a Londoner, but a Surrey native. His connections to Surrey, however, were not particularly heartfelt: when he later looked back on the matryoshka of suburbs where he had his roots, he neither voiced regrets that he had to leave it, nor harboured a wish to return. Culturally, he perceived it as a dead end and opined that musically “nothing ever happened there”[21] - although it needs to be noted that the renowned folk guitarist Whizz Jones was born in Thornton Heath four years after Royston, in 1939. What Royston meant to say was probably that the Croydon Borough was not urban enough to spawn an inspiring musical scene, but had become too urban to maintain a folk music tradition. The latter aspect explains that when Royston later became a folk singer, and those fellow folk singers with a conservative stance issued the doctrine that folk singers should only sing songs from their birthplace, Royston joked that collecting folk songs from suburban Surrey would have been like “collecting songs from Regent’s Park”[22], an uninhabited greenland in North London. What he thus suggested was that, had he earnestly and strictly complied with the aforementioned ‘only from your own backyard’ rule, he would never have become a folk singer, just because he would not have found anything reasonable to sing.

Eventually, Surrey turned out to be Royston’s home only for a very brief time: contrary to many children who were stuck in their safe and boring suburbian cul de sac until they could break free from their petit-bourgeois cage in their late youth or early adulthood – the archetypal rock’n’roll trajectory –, Royston’s protected childhood in Surrey was suddenly interrupted when, aged four, Germany commenced the second world war. The time frame for Royston’s childhood years is ragged, but with information provided by himself in an interview, and additional memories shared by his second wife Leslie, the following story unfolds:

When the war started, the population of the Croydon borough feared German air raids, as Croydon harboured major British infrastructures, including Croydon Airport, Britain's main airport at the time. Thus, Royston was removed from his family, and – aged about 4 – evacuated into a temporary care family in the Southern English countryside[24]. Meanwhile, the family prepared to relocate to Scotland where Royston’s father was assigned to do “top secret” work for the BBC in the Scottish town of Fraserburgh, Aberdeenshire[23]. Royston himself later remembered his evacuation, and particularly his stay with the shelter family as debilitating: far away from his parents, he suffered severe bouts of asthma and was generally in frail health, when his mother Constance “'rescued' him from the family looking after him - just in time (according to Royston's memory)” and reunited him with his kin[25].

To today's readers it might sound strange that a child who was brought into safety was yearning to return to the place where the bombs were coming down. John Foreman (1931 - 2024), a London folk singer roughly from Royston's generation who was not evacuated, offered an explanation, and suggested in an interview with Mike Butler that the London children who got evacuated were probably safer than those who stayed, but were probably subject to higher mental distress: “Kids had a lovely time. The ones who were evacuated weren’t so happy, but those of us who were here [in London], yes. School was a joke! I used to collect shrapnel. It was a great thing, first thing in the morning, going out, seeing what had been bombed, digging out the bits and pieces, finding bits of guns. We were able to play about on bomb sites. Oh, it was very jolly.” The statement, which is certainly not devoid of irony, and possibly sounds crude from an adult's stance, is indeed understandable from a child's perspective: being with one's family and playing in what a child interprets as an adventure playground might feel like an easier life than living in a protected, but strange place and suffering from homesickness - as Royston apparently did in a severe form.

Eventually, the Wood family settled in County Moray, Scotland, in the environment of the town Elgin, about sixty miles west of Fraserburgh[26]. From then on, Royston had to come to terms with a cold and ragged part of Britain, opposite to the milder Southern English realms where he spent his first four years. Not surprisingly, the war was an unhappy time for the Wood family: although Scotland was probably less endangered by the blitzkrieg than London and the English industrial towns, the Germans also conducted attacks against Scottish coastal towns, for instance dropping bombs on Clydebank in 1941. Apart from the frightening war situation, the economic circumstances for the young family were just as horrible: the Woods, like many English families during the war, were „dead broke“[27] during the war, and could not even afford the usual household objects of the time - including the grammophone, which would have been a most beneficial addition to that very musical household. Hence, the only two ways for the family to access music were the radio receiver and house music sessions. Since Constance had some command of playing the piano, and since there was a lone piano standing in their Scottish home where “Mum dug out all these pieces of sheet music from God knows where, I think they all came from the piano stool”[28], there was at least some opportunity for domestic music to lighten up the glum atmosphere.

Other than the sorry economic situation of the family not much is known about Royston’s childhood in Scotland. However, his involuntary second home exerted a lasting influence on his musical work, and throughout his whole life Royston displayed a friendly inclination towards Scottish culture. He was, for instance, fond of Scottish bagpipe music[30] and also enjoyed interspersing Scottish folk songs into his otherwise English repertoire from time to time[31]. The Scottish dialect also served Royston as a source of affectionate comedy, when during his concerts he occasionally improvised rambling monologues in dialect – possibly impersonating characters he encountered during his childhood – and also succeeded in making his “humorous readings” of William McGonagall’s “flagrantly bad” poem The Tay Bridge Disaster a comedic high point of his concerts[32]. Probably, Royston’s childhood proximity to the raging North Sea also predilected him to two of the folk song types he came to like the best – the sea chanteys, and maritime ballads about life on sea[33]. Not least it is notable that, when Royston died, his friend David Amram bid him adieu singing one of the quintessential Scottish folk hymns, Wild Mountain Thyme, the first verse of which is also engraved in Royston’s tombstone, suggesting that this song bore some significance for him[34]. However, Royston never felt the urge to return to live in Scotland; instead, he cultivated a lifelong infatuation with warm coastal areas which somehow gives the impression of a prolonged reaction against the barren Northern landscapes he was forced to inhabit in his yore[35].

Although Royston’s recollections give the picture that his parents had tried their best to provide him with a safe and nurturing family environment, the outer circumstances of his childhood were obviously less than idyllic. It appears as if immersing himself in symphonic music – which Royston used to refer to somewhat crudely as “straight music”[36] – provided him with a safe, colourful and vivid inner world that was soothing, compared to an outer world that was barren and frightening during the war, and that turned towards the dull and anemic in the post-war years. Throughout the war Royston would receive very basic musical education from his mother, who would accompany herself on the piano when “she’d sing selections from Gilbert and Sullivan”, the librettist-and-composer duo who wrote comedic operas in the 19th century, and “[young Royston would] join in“ and sing along with his mom[37]. Royston did not mention that his father taught him how to actively produce music, but suggested that he implicitly taught him how to listen to music: Charles was described by his son as “a BBC nut [who] always had some kind of radio” and enjoyed discovering new music during extensive radio listening sessions, to which young Royston used to come along: “I was mostly inspired by music on the radio. [...] You’d be surprised at how much music they used to play on the radio”[38]. When for Charles listening to the radio was not a mere pastime, but also a professional obligation owing to his job in the secret service (“He had to keep topside of things when he wasn’t at work”[39]), the father’s occupation turned out to be the son’s delight: Royston disclosed his younger self’s favourite radio programme as Those You Have Loved on the BBC channel Home Service – the predecessor of BBC Radio 4 – in which Doris Arnold presented “light classical recordings”, lighter certainly than the classical music Royston would adher to later: “There was a fair amount [of music in the house] actually, [but] it wasn’t the kind of music that you’ll find in my house”[40,41]. Nonetheless, what he heard there became the groundwork of his later work: “In those days The Home Service was a bloody marvellous piece of work, I thought. [...] [It turned me on] to classical music […] very early on”[42].

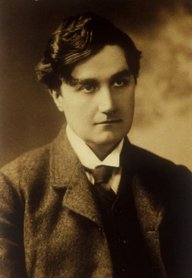

The composers whose names Royston specifically dropped when he spoke about his earliest musical experiences were mostly the established Central European masters such as Georg Friedrich Händel – he first encountered the aria O Lovely Peace from the opera Judas Maccabaeus aged 5[43] –, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Ludwig van Beethoven – he especially praised his late piano sonatas and the Symphony No. 3 („Eroica“), which contains a modulation “from major to minor, or the other way round” which always “made him cry”[44]. He also counted among his “heroes”[45] three relatively contemporary composers from the Anglophonic world: the two Englishmen Gustav Holst and Ralph Vaughan Williams as well as the Australian Percy Grainger.

Vaughan Williams’ and Grainger’s compositions eventually became Royston’s musical bedrock. Both composers, incidentally, stood out from many of their contemporaries in that they were not only considering the canon of classical music in their works – for Vaughan Williams, his teacher Hubert Parry (1848 – 1917) was an outstanding source of inspiration –, but were also associated with the First British Folk Revival and, thus, very conscious of the corpus of traditional English folk songs: those old songs that the rural pre-radio/pre-grammophone generation had learned by oral tradition from their forefathers and -mothers, songs whose composers or origin was indeterminable because the songs were so old and had gone through so many iterations of the tradition process that they had developed a life of their own. Although Vaughan Williams – who, on a side note, was biologist Charles Darwin’s grandnephew – had been aware of this ancient music since his early days, it was in the earliest years of the 20th century, when as a 30-year-old man he made a late start into becoming a composer, that he set out to the British countryside himself to systematically collect folk songs from the surviving source singers. Vaughan Williams’ approach was not new: already in the 18th century the German authors Clemens Brentano and Achim von Arnim had published Des Knaben Wunderhorn, an edition of German traditional folk songs they had collected and collated on their research trips into German villages. However, as both men were poets, they were exclusively interested in the lyrical side of the songs and did not provide the tunes to the songs in their seminal publication. Vaughan Williams’ English predecessors, including Cecil Sharp (1859 – 1924) and Lucy Broadwood (1858 – 1929) and her uncle John (1798 – 1864), were more musically inclined in their invaluable ethnomusicological research. As a professional musician, Vaughan Williams’ focus on the musical substance was even stronger, and he dedicated a lot of time towards analysing as many musical nuances in his source singers’ delivery as possible.

One folk song that was an especially crucial experience for Vaughan Williams, and by proxy also became a crucial experience for Royston, was the traditional English carol Dives and Lazarus, the story of which Royston poignantly summed up as: “This did happen, so we’re told: it’s rich man Dives, or Diverus as he turns out in the song, and Lazarus the beggar, who’s asking for grub and doesn’t get any. But he goes to heaven – hooray – and Dives goes to hell – hrm. It just shows you how simple morality was in those days”[46]. Vaughan Williams had already heard the song a couple of years earlier, but first collected it formally in 1904 from the village of Kingsfold near Horsham, West Sussex. He later mused about his archetypal feelings that his immersion in the tune evoked: “I felt like this when I later heard Wagner, when I first saw Michael Angelo's Night and Day, [and] when I first visited Stonehenge. I immediately recognised these things which had always been part of my unconscious self. The tinder was there, it only wanted the spark to set it ablaze... So when I first played through Lazarus, I realised that this was what we had all been waiting for—something which we knew already—something which had always been with us if we had only known it; something entirely new, yet absolutely familiar”[47]. During the course of his field work, Vaughan Williams encountered not only one, but several versions of the popular tune from various people, amidst dozens of other folk songs he collected and wrote down. In 1905 the main phase of his collection work ended, and as he became a composer of increasing renown towards the 1910s, elements, quotes or just moods emanating from the folk songs he had collected would diffuse into his compositions time and again, inhabiting them like friendly spirits.

In the case of Dives and Lazarus, however, it took many years until Vaughan Williams distilled his initial epiphany into a distinct composition: when he was about 65 years old, the composer, taking a trip down memory lane, resorted to the tune and forged it into the 13-minute orchestral piece Five Variants of Dives and Lazarus – the title of which does not refer to ‘variations’ within the sense of classical music, but indeed to ‘variants’ within the sense of folk music, as the composition reflects the different versions of the tune Vaughan Williams had collected in different villages during his research. The composition, written on commission from the British Council for the 1939 New York World’s Fair, was debuted in Carnegie Hall, New York, on June 10 1939 to the great acclaim of reviewers who praised Vaughan Williams’ “return, after recent excursions in other fields, to modal harmonization and modal counterpoint, which he loves and he writes so well”[48]. It did not take long until it was also performed in England as well. At some point in 1940, when Royston sat in front of the radio receiver with his father Charles, a radio programme – “you’d be surprised at how much music they used to play on the radio”[49]– must have featured Vaughan Williams’ Dives arrangement and caught the child’s attention. Just like working with the Dives tune had been a transcendent experience for Vaughan Williams, listening to Vaughan Williams' orchestral arrangement turned out to be a transcendent experience for young Royston, who would remain in awe about the piece, and never ceased to refer to the tune and Vaughan Williams’ orchestral arrangement as he moved on with his own music.

Taken together, Royston, by his time of birth and by the realms he grew up in, happened to take roots in the very end of the musical era of romanticism[50], which, although it had already begun way back in the late 18th century, still proved able to spawn a late blossom in England through people like Vaughan Williams and Holst. For Royston, thus, late romanticism was not a music of a distant past, but music that was still, if narrowly so, music of his own time and age.

Royston’s deep infatuation with classical music contrasts with the poignant circumstance that he neither learned how to play an instrument, nor received any formal musical training during his childhood. He was neither particularly versed in reading sheet music nor in musical terminology – a shortcoming that lasted well into his adulthood. His father had already retired from his sidejob as a wind instrument player for the aforementioned dental reasons, and did not assume the role of Royston’s private music teacher. At least, on the practical side, Royston could nick some vocal techniques from his mother by imitation. Although as an adult Royston frequently repented his lack of formal training, it is unknown if as a child he had unsuccessfully asked for a proper musical education and was turned down for economic or logistic reasons, or if young Royston was actually content to have his private, unadorned and childlike fun with classical music – without teachers telling him what is right and what is wrong. There could be some truth to the latter, as Royston – slightly proud of his independent mind – described his younger self’s approach to music as intuitive and playful rather than academic and orthodox: „I used to wander round singing bits and making up words to silly tunes and singing variations“[53]. Royston remembered well that he had always had a natural inclination towards counterpoints rather than the main voice of a piece: “Ever since [the] early days, whenever I’ve listened to symphonic music I’ve always followed the things that wove around the tune rather than the tune itself, the things that implied the tune"[54]. Above all, the lower parts of the score, the “cellos and basses and bassoons, [the] French horn”[55], caught his interest, which later proved beneficial when his voice fell into the bass-baritone range, which encompasses a similar frequency spectrum to the aforementioned instruments. All of these early experiences marked the foundation of how Royston – despite being a non-instrumentalist – became a „creative listener“ with a „very discerning ear“[56] quite early in his life, and thus in some way a natural music critic, who would always develop and also display strong feelings about the quality and overall coherence of music he was confronted with.

When the second world war came to an end, Royston was ten years old and still living in County Moray with his family[57]. As he himself remembered, the war circumstances had forced him to change school multiple times[58], which made him a vagabond already at a young age, not unlike his far-travelled father. There is no further information about Royston’s high school years, other than the surmise that they were probably not the finest years of his life. The subtext of the available sources vaguely suggests that he was a creative and perceptive pupil with a good feeling for language, but not particularly ambitious as far as excellent marks were concerned. He was also devoid of a determination to strive for a certain profession (which not all, but at least some children display in their early teens), and possibly, overall, bored by the sheer concept of school. Certainly, the average teacher of the 1940s used to be more authoritarian, and more reckless in subjecting their pupils to strict frontal lectures that were devoid of genuinely interactive or creative moments. Consequentially, Royston dropped out of the school system fairly early, in the “late ‘40s, early ‘50s” when he was about 15 years old, right after finishing his O (Ordinary) levels[59]. At such a young age, after a very fragmented childhood and robbed at least partially of his youth by the war, it was not surprising that Royston “didn’t know what [he] was going to do really”[60]. Due to his lack of musical training a career as a musician was totally out of reach and nothing he could even wish for. His school years had seen him displaying a talent for writing which awakened adolescent daydreams about a life in literature: „I wanted to be a writer (laughs), I wanted to write significant novels, poetry and things of that sort“[61]. Coming from a poor middle-class family, the decision he eventually took was less eccentric: when Royston, aged about 16, enrolled at Brighton Technical College – a kind of polytechnic college – for a Bachelor of Science in Economics[62], it sounds as if he acted upon the rational impulse of striving for a safe job rather than the breakneck impulse of starting an uncertain life in the fine arts. As most academic studies demanded a higher qualification than Royston’s very basic O-levels, his admission to this particular bachelor seemed to be an opportunity to make the best out of his situation: to get an academic degree, a job in the industry and maybe a chance for a life in prosperity which his parents could not provide to their children. Although his youthful inscription in a college allowed Royston to escape from a confining life in Scotland, which probably was good news to him, he was unable to warm up to becoming an economist and did not stay long, quitting college shortly after his new life had begun[63].

The next step of his career came by chance and, indirectly, courtesy of his little brother Graham, who was in need of some assistance in his schooling: “[Graham had a hard time in school], and my mother would shift him round trying to find a school that would take him and be good for him. She found this school where the fees were something ludicrous like £40[64] a year"[65]. It turned out that the same “dreadful little private school” – a so-called ‘cram school’, as Mike Butler noticed while proofreading this text – was in dire need of teachers[66]. For the lack of better options they employed 16-year-old Royston as an unqualified assistant teacher: “I ended up a teacher at this place for 18 months or so, absolutely dreadful, like getting kids though their GCE and poetry perception exams and I’d only passed the damn things myself. Amazing. I had no sense of direction”[67]. Despite the peculiar situation, Royston was able to make his first working experiences, and specifically his first steps as a teacher, which – directly or indirectly – would remain one of his central occupations throughout big parts of his life.

It was during his employment there that Royston also got acquainted with a woman named Denise, who was about 23 or 24 years old, that is roughly five or six years older than him, and was working as a graphic designer in an advertising agency[68]. Royston quit his school job, and it was not long until the couple married. His wife introduced him to the advertising industry, where, as an able employee, he took satisfying steps upward on the corporate ladder: he started as a regular clerk for the Regent Oil Company, before he switched to the P. R. department of the food company Energen Foods[69], which produced bread rolls that promised to help people lose weight. Although his job profile allowed him to write texts, an activity which Royston principally enjoyed, he remembered the precise tasks he was required to do as fairly dull: „[T]he function of a P.R. writer was to find what kind of formula letter to send out to all these people who wrote in enquiring what kinds of slimming foods were best for them, calory diets and things like that, the work was incredibly tedious“[70]. He did not stay long and moved on to work as a “medical copywriter” for the London office of the US-American pharmaceutical company Smith, Cline & French, based in Philadelphia, PA, among whose brands he especially remembered the amphetamine-based substances benzedrine and dexedrine - the former of which people used as a spray against congested noses (taking the psychotropic side effects into account), and the latter as pills or an elixir to purposefully stimulate their minds. He wrote promotional and informational texts for the firm, and remembered that – although it was a weird job – it was at least the most financially rewarding among his corporate employments[71].

Although Royston’s life in the mid-1950s seemed not particularly eccentric – rather a typical life one would expect in an English middle-class family – Denise, employed in the artistic and creative branches of the advertising industry, was friends with the „art school crowd“[72]. One of her colleagues at work, a fellow designer, had in the early 1950s become part of a strange avantgarde that was taking interest in traditional folk music, a part of English culture that was nearly forgotten in post-war Britain and only cultivated by two fairly disparate groups: the very old people who knew the music from ages past, and a small group of left-leaning and progressive eccentrics who were keen on unearthing and reviving this buried cultural treasure; obviously, his wife’s colleague was closelier affiliated to the second group than to the first. When Royston became conscious of the scene, his wife’s workmate already possessed what appeared to Royston as “the biggest collection of folk music in the country”[73]. Royston was inspired by their mutual friend, followed his example and invested parts of his income to “buil[d] up a fair record collection” himself, and although the bulk of it was classical symphonic music, the first folk records found their way into his shelf as well, including “some nice ones, Cisco Houston and some early Pete Seeger things, I really like Rambling Jack [Elliott], Ewan [MacColl] and Peggy [Seeger], Shirley Collins”[74]. The music Royston discovered there brought a new American influence into his musical world, a world that had previously almost exclusively been dominated by European, and especially English music. Apparently, Royston developed some sympathies for the American sound with its bluesy inflections, the sound of guitars and banjos, and the rustic mountain atmosphere of Appalachia - music that was less elegant than the European music, but earthier, and laid greater focus on personal expression.

A bit later, roughly between 1953 and 1955, the mutual friend (name unknown) also introduced Royston and Denise to the first London folk club: the Ballads & Blues club that had recently been founded by the two senior folk song specialists Ewan MacColl and A. L. Lloyd. It operated at the Princess Louise pub in High Holborn, Central London, where Royston met some of the names he knew from his LPs. The difference between the residents and his family roots could not have been bigger: although MacColl, born 1915, and Lloyd, born 1908, belonged to Royston’s parents’ generation, their respective biographies represented the absolute opposite of the “unadventurous yeomen stock” that Royston saw in his parents: Lloyd, a member of the Communist Party, had spent his whole life as a day labourer, working here and there – for instance on a sheep farm, a whaling ship, or, in 1937, translating Frank Kafka's seminal Metamorphosis into English – and spent those invaluable weeks when he was unemployed with autodidactic studies of folk song, until he became an acclaimed folk singer and self-made folk song scholar. MacColl, also a communist and sometimes described as “the English Brecht”[75], was a folk singer, actor and theatre director who had made his a name with various radically provocative theatre plays. To him, English folk song was not only an art form, but also the property of the English workers and peasants, and thus inherently political. Like Lloyd, he was living from day to day, earning his money from various little jobs, and dedicating his idle days to autodidactic studies of folk song and literature.

The circuit Royston was getting involved in, courtesy of his wife Denise, turned out to be formative for his later endeavours: “I saw a lot of people there who became colleagues many years later, 10 or 12 [years] actually, and I got turned on to American and English traditional music”[76]. Two of the younger singers who were already visible in the London folk club scene in the 1950s, and who would become closer friends for Royston later were Louis Killen, a singer from Newcastle who was about a year older than Royston, and the experienced Sussex singer Shirley Collins, who was a few months younger than him, and in a romantic relationship with the acclaimed American ethnomusicologist and singer Alan Lomax.

However, despite the exciting company Royston was enjoying, he did not let the musicians and politicians draw him into their ideological or artistic currents, but retained his independence at the time. Neither did Royston engage with the rock’n’roll genre that was gaining popularity at the time: he rather stayed true to his beloved symphonic music: “If I wanted a charge musically then I’d go to the Festival Hall or some place like that and listen to straight music, or listen to my records“[77].

An instrument which Royston would occasionally see in the club was a little octagonal squeezebox that was competently played by a man in his mid-50s who was not a singer, but used the little box to accompany those who did sing on stage: both MacColl and Lloyd had chosen the English concertina as their favourite instrument for the purpose of accompaniment, and Alf Edwards in particular as their key accompanist. In principle, the two singing communists were firm adherents to the traditional way of singing – in England, through all the previous centuries, folk singers had never sung to instrumental accompaniment, but always a capella – and would have loved to sing their songs as simply as their predecessors. However, as most people in the post-war time were not used to listening to unaccompanied voices any more – the old days of unaccompanied rural singing on village festivities were long gone –, and as MacColl and Lloyd had the fervour of convincing the same common people of the validity of folk music, they felt the need to compromise with the listening habits of their audience. As MacColl and Lloyd wished to establish a specifically English folk music, they wanted their voices to be surrounded by an autochtonous English sound, and not by instruments imported from America. Although the American musician Peggy Seeger, the half-sister of Pete Seeger who became MacColl's girlfriend in 1956, brought in her guitar and banjo into the clubs a while later, the English concertina – old-fashioned, though, it was – became the most emblematic instrument for the core English folk revival. Certainly, its chromatic buttons which provided all semitones of the scale, its inherent restraint and lovely sound – flutey and sweet, but also clear and cutting – helped the little box on its rise from an existence as a compromise solution to attaining a reputation as one of the most tasteful, versatile and respected instruments in English folk song accompaniment.

Alf Edwards had been born in 1903, at the end of an era in which the English concertina had been a fashionable instrument for amateur family music and had played a comparably prominent role to the guitar and the piano nowadays. Edwards came from a family of itinerant circus showmen, who always had to learn new instruments just like they would have to learn new tricks to avoid boring their audiences. Thus, it was neither pure eccentricity nor an attention disorder, but a mixture of a great musicality and sheer economic necessity that had turned Alf, who had started playing the concertina at the age of 5, into a proficient player of the “fiddle, trombone, ocarina, alto-saxophone, clarinet, piano, great-highland-bagpipe and drums”[78] at a fairly young age. His contemporaries remembered that Edwards' background with regards to the English concertina did not lie in folk music, but in classical music, which also meant that Edwards was never seen playing without a sheet music: "I have an image of Alf Edwards with a music stand in front of him in his house, in his music room, playing a violin concerto by Bch or one of his contemporaries - that's what Alf loved to play. On this beautiful, sharp, bright metal-ended Aeolian that he played."

From these roots, his concertina accompaniments stretched into the folk scene – a less attention-seeking domain than the itinerant showbiz –, where Edwards was allowed to put his musicality into the service of the brilliant songs that Lloyd, MacColl and the other singers had in store. The younger generation took good heed, and some of the young singers visiting the club learned to play the English concertina as well – an instrument that was relatively cheap, useful and easy to play at least on a basic level. The aforementioned Louis Killen was one of these concertina novices, but distinguished himself from Edwards in that he used it to accompany his own voice, just like the American folk singers who were accompanying themselves on the guitar. Killen was not only fascinated by the instrument, but also by Edwards, reminiscing: "This man was the most incredible transcriber of music I've ever come across. He could transcribe music that he listened to faster than you could write a letter." When Killen started his own folk club in the Northern English miners’ town Newcastle-upon-Tyne in 1958, he would increase the unusual instrument's reputation there as well.

Royston, who was visiting the Ballads & Blues and its London spin-offs only occasionally, surely observed what was happening in the scene and was at least mildly interested by what he observed. Certainly, it also did not escape him that A. L. Lloyd, that friendly tenor singer who treated his audience to wonderful traditional ballads, was friends with Royston’s classical music hero, the venerable Ralph Vaughan Williams, and that the two musicians were preparing the results of their respective field research work for a book aimed at the broad public, which eventually became The Penguin Book of Folk Songs, later to be published by Penguin Books Ltd. in 1959. Not least, the role distribution between Lloyd as the singer and Edwards as his accompanist – allowing Lloyd to focus on the singing, and Edwards to focus on the accompaniment – might have reminded Royston of the performance practice in the romantic art song of the Schubert and Schumann type: with the two differences that the folk singers used to sing in a straight way, not in classical belcanto, and that the piano’s role was taken by its little portable working-class sister, the English concertina.

The social, political and intellectual dynamics in the folk scene proper, however, did not seem to be incredibly relevant for Royston on a personal level; folk music was something that mainly happened outside, not inside of him, although the seeds of a tender infatuation were already sown: “[I] never did anything about [folk music] particularly. [I] collected a few records, learnt a few songs, but never used to sing them [in public]”[79]. Despite the tentative budding of a repertoire, in 1957, it was to take about five more years until Royston first stood on a folk club stage and sang, and about a dozen of years until he would follow Edwards’ and Killen’s lead by deciding to pick up the English concertina as well.

A while later, when Denise was in her late twenties, Royston – still in his early twenties, and still busying himself with his corporate jobs – became a young father to his first daughter, who was likely born at the end of the decade, around 1958 or 1959. The second child, Royston’s only son, followed on June 7 1960[80]. Married with two kids, equipped with a decent job and associated with an edgy metropolitan music and arts scene, 25-year-old Royston’s life in 1960 was a veritable middle-class post-war success story which fulfilled all of society’s demands. Given time, Royston, an intelligent and creative young man, could look forward to climbing up the corporate ladder even higher, maybe eventually even reaching a well-paid leading position in a high-revenue industry.

Footnotes:

[1] Pat Woolf, a friend of Royston's, vaguely remembered that they shared the same birthday. His former wife Leslie Wood agreed that this likely was his date of birth. Other sources for his birthday do not exist.

[2] Transcript of the banter of a Swan Arcade gig in St Andrews, April 29 1973

[3] Interview with Royston Wood, ca. March 1977, conducted by Owen Jones, published in Albion Sunrise magazine, p. 39, issue 3, 1984, edited by Owen Jones

[4] Royston’s appearance on Findagrave; https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/80410152/royston-michael-wood, retrieved on August 3 2025

[5] ibid.

[6] The transcript of Royston’s interview is imprecise as to if the post officer was Constance’s father or Royston’s father; the context gives the impression that Royston’s maternal grandfather was the post officer.

[7] The Surrey Mirror and County Post (Reigate, Surrey), July 21 1916, p. 5, retrieved from www.newspapers.comon Fri, 5 2025

[8] Interview with Royston Wood, ca. March 1977, conducted by Owen Jones, published in Albion Sunrise magazine, p. 39, issue 3, 1984, edited by Owen Jones

[9] Royston’s former wife Leslie said in a June 2025 interview: “If his mother was an opera singer, I don't recall her ever performing anywhere.”

[10] Reigate History - 1920s/30s

[11] Interview with Royston Wood, ca. March 1977, conducted by Owen Jones, published in Albion Sunrise magazine, p. 39, issue 3, 1984, edited by Owen Jones

[13] Interview with Royston Wood, ca. March 1977, conducted by Owen Jones, published in Albion Sunrise magazine, p. 39, issue 3, 1984, edited by Owen Jones

[14] ibid.

[15] ibid.

[16] Interview with Royston’s daughter Rachel, May 2025.

[17] Graham is still alive at the time of writing, and briefly corresponded with the author in 2025.

[18] Interview with Royston’s former wife Leslie, June 2025.

[19] Interview with Royston’s daughter Rachel, May 2025.

[20] Transcript of the banter of a Swan Arcade gig in St Andrews, April 29 1973

[21] ibid.

[22] ibid.

[23] Interview with Royston Wood, ca. March 1977, conducted by Owen Jones, published in Albion Sunrise magazine, p. 39, issue 3, 1984, edited by Owen Jones

[24] Interview with Royston’s former wife Leslie Wood, June 2025.

[25] ibid.

[26] At least, County Moray was given as the region where Royston’s mother lived, and Elgin as the town where Royston’s sister lived when he died.

[27] Interview with Royston Wood, ca. March 1977, conducted by Owen Jones, published in Albion Sunrise magazine, p. 39, issue 3, 1984, edited by Owen Jones

[28] ibid.

[29] Murdochs-Wynd-Elgin.jpg (1427×901)

[30] In 1980, he enthusiastically supported a group of young Canadians, Na Cabar Feidh, who played their arrangements of Scottish bagpipe music, and featured their music in a radio programme about him.

[31] Johnny O‘Braidislee and Twa Corbies were two favorites.

[32] Ilana Pelzig, for Walrus Issue #192, August 25 1976, p. 27; Pelzig would later do technical work for Richard Thompson on some of his albums.

[33] Two of his favourites were The Rainbow about a heroic shiplady who successfully fought off an enemy attack after the male crew members had fallen, and The Weary Whaling Grounds, about the economic and emotional exploitation of the whaling crew members on a Greenland expedition.

[34] The online version of Royston’s grave, retrieved from: Royston Michael Wood (1935-1990) – Find a Grave Gedenkstätte

[35] As a young man he would enjoy tramping to the Isles of Scilly. In his thirties he dreamed about an artist’s life on a detached Greek island. In his fourties, when living in New York, he planned on moving to San Francisco, before fortune decided otherwise.

[36] Interview with Royston Wood, ca. March 1977, conducted by Owen Jones, published in Albion Sunrise magazine, p. 41, issue 3, 1984, edited by Owen Jones

[37] ibid., p. 39

[38] ibid.

[39] ibid.

[41] Interview with Royston Wood, ca. March 1977, conducted by Owen Jones, published in Albion Sunrise magazine, p. 39, issue 3, 1984, edited by Owen Jones

[42] ibid.

[43] Transcript of Royston’s appearance, entitled ‘Concertina and capella’, on Edward Haber’s radio programme The Piper At The Meadows Straying, January 1978.

[44] Transcript of Royston’s concert at the Eisteddfod at the University of Massachussetts, autumn 1978

[45] ibid.

[46] ibid.

[47] Vaughan Williams, Ralph (2008). Manning, David (ed.). Vaughan Williams on Music. Oxford University Press, p. 252

[48] Simeone, Nigel (2022). Ralph Vaughan Williams and Adrian Boult. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press, pp. 174-175.

[49] Interview with Royston Wood, ca. March 1977, conducted by Owen Jones, published in Albion Sunrise magazine, p. 39, issue 3, 1984, edited by Owen Jones

[50] The author is aware that Vaughan Williams’ belonging to the romantic tradition is disputed, and that sometimes he is even referred to as a ‘post-romantic’ composer. However, the author argues that Vaughan Williams was certainly connected with the romantic tradition, even if he transcended it in his works.

[51] NPG x2377; Ralph Vaughan Williams - Portrait - National Portrait Gallery- RVW 1938

[52] Lucy Etheldred Broadwood - Person - National Portrait Gallery

[53] Interview with Royston Wood, ca. March 1977, conducted by Owen Jones, published in Albion Sunrise magazine, p. 39, issue 3, 1984, edited by Owen Jones

[54] Edward Haber

[55] Transcript of Royston’s concert at the Eisteddfod at the University of Massachussetts, autumn 1978

[56] Interview with Royston Wood, ca. March 1977, conducted by Owen Jones, published in Albion Sunrise magazine, p. 41, issue 3, 1984, edited by Owen Jones

[57] ibid., p. 39

[58] Liner notes of Royston Wood & Heather Wood’s LP No Relation, Transatlantic Records, 1977

[59] Interview with Royston Wood, ca. March 1977, conducted by Owen Jones, published in Albion Sunrise magazine, p. 39, issue 3, 1984, edited by Owen Jones

[60] ibid.

[61] Edward Haber

[62] Interview with Royston Wood, ca. March 1977, conducted by Owen Jones, published in Albion Sunrise magazine, p. 39, issue 3, 1984, edited by Owen Jones

[63] ibid.

[64] circa £1150 in 2024

[65] ibid.

[66] ibid.

[67] ibid.

[68] Interview with Royston’s former wife Leslie, June 2025.

[69] Interview with Royston Wood, ca. March 1977, conducted by Owen Jones, published in Albion Sunrise magazine, p. 39, issue 3, 1984, edited by Owen Jones

[70] ibid., p. 40

[71] ibid.

[72] Interview with Royston Wood, ca. March 1977, conducted by Owen Jones, published in Albion Sunrise magazine, p. 40, issue 3, 1984, edited by Owen Jones

[73] FBBS interview

[74] Interview with Royston Wood, ca. March 1977, conducted by Owen Jones, published in Albion Sunrise magazine, p. 41, issue 3, 1984, edited by Owen Jones

[75] Abstract of Class Act: The Cultural and Political Life of Ewan Maccoll, by Ben Harker, Pluto Press

[76] Interview with Royston Wood, ca. March 1977, conducted by Owen Jones, published in Albion Sunrise magazine, p. 40, issue 3, 1984, edited by Owen Jones

[77] ibid., p. 41

[78] Portrait of Alf Edwards on raretunes, Alf Edwards – rareTunes, retrieved on August 3 2025

[79] Interview with Royston Wood, ca. March 1977, conducted by Owen Jones, published in Albion Sunrise magazine, p. 40, issue 3, 1984, edited by Owen Jones

[80] Interview with Royston’s daughter Rachel, May 2025.